I’ve been thinking about self-care for writers a lot lately.

|

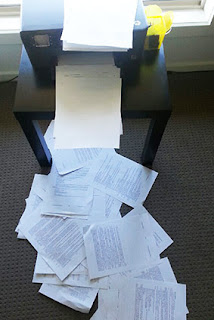

| Life. Sometimes it's like this. |

And I

realised during an interview with IH Laking for his blog, when he asked me about tips for

moving into writing full-time after a career in another field, that I fall firmly into the 'learn from my mistakes' camp. In hindsight, I tried to do too much too soon and it contributed to an episode of depression.

Chuck Wendig and Madeleine Dore both offer some sage advice about looking after yourself as a writer, much of which is relevant for anyone working from home or in creative fields where contact with the outside world can be limited.

Chuck Wendig and Madeleine Dore both offer some sage advice about looking after yourself as a writer, much of which is relevant for anyone working from home or in creative fields where contact with the outside world can be limited.

While

Chuck’s article is aimed mainly for published authors – you don’t need to read

all your reviews and don’t have to yell back at people on the internet, for

example – he also discusses the difference between writer’s block and depression,

dealing with shame, comparing yourself to others, having a life outside writing,

and treating your body as a machine with dongles that need cleaning and widgets

that demand waxing.

Madeleine’s

article focuses on burnout and fatigue, linking low pay rates with an inability

to say no to work. Through interviewing several arts professionals, she notes the

importance of self-care and self-awareness in countering isolation, mental

health, doubt and exhaustion.

The

take-home message from each article: You can’t do the work if you physically

and mentally can’t do the work.

Chuck’s

point about writer’s block versus depression hit home, because this is what I

went through two years ago.

I was

studying full-time, caring for a high-needs child, and trying to get my fiction

career off the ground. I was seeing a physiotherapist about recurring pain,

numbness and tingling in my left arm and hand.

My

husband took a redundancy from work, retrained, then struggled to find permanent

work. This coincided with my symptoms worsening. Suddenly the nerve issues

changed to my right hand and arm. I was dropping things because I was losing

sensation in my hands. At night, I woke constantly with numb arms.

I was referred

to a neurosurgeon. An MRI showed two levels of vertebrae in my neck pressing on

my spinal cord, changing the cross-section from circle to a C-shape. The move

from left to right was called a ‘signal switch’ – it was a serious symptom.

Next to go would be my bowel, bladder and legs.

I was

booked in for surgery on the next available date. Best case I’d be in a neck

brace for two weeks, worst case six.

I wore that

damn thing for ten weeks over summer, couldn’t lift anything over one kilogram or

raise my arms over my head for ten months. I have permanent lifting limits and restricted

movement in my neck.

The neck

brace came off a few days before uni started. It’s all online, I’m sitting at a

desk. Easy, right?

Wrong.

I had to drop

back to part-time study, and I this felt like a failure. My husband was working

two hours away and doing the bulk of the housework because I couldn’t do basic chores,

and this made me feel useless. Our son was acting out because I ‘was sick’ and

he’d been told by people before us that his birth mum couldn’t look after him

because she ‘was sick’, and this made me feel like a crap parent. I scraped

through that semester with decent marks but needed and extension for every

assignment – on doctor’s orders – and this made me feel like a slacker and more

of a failure.

I’d been

out of the neck brace for six months when the second semester started, and my

recovery wasn’t progressing as well as it should be.

Then came

the clanger – a writing assignment in which we examined our experience with a

political or social issue. I wrote about the process of becoming a permanent

carer, and the reactions of some people once they realised our son had been in

foster care.

The grief

and shame of not being able to have children, the intrusion and uncertainty of

the application process, the joy, fear, isolation and utter helplessness of suddenly

parenting a traumatised child were compressed into a 2500-word assignment.

I wrote

it, it was workshopped, and I didn’t look at it for two months. I couldn’t. It

compounded the failure, uselessness and general craptitude I was feeling.

I started

withdrawing from my family, pushing myself harder to write and study and enjoying

it less and less, and slamming myself for every minor setback. I thought my

inability to write was a severe case of writer’s block, which I’d never experienced

before. As a journalist, I couldn’t afford to. I always wrote through it.

Driving

home from somewhere one morning I started planning how I’d leave – not because

I was unhappy, but because I was convinced they’d be better off without me. We

were in danger of losing our house and I couldn’t work so that was my fault, I

was a crap parent, could barely do anything around the house, had made a career

move into a field that was less stable than the one I’d left. I couldn’t think

of a single way that me being part of my family was a positive for anyone. I came

close to throwing my phone out the window and driving until the petrol ran out.

Or until there was a curve in the road I might miss.

Instead,

I drove home. I took online depression tests through Beyond Blue and the Black Dog Institute. I called my GP. I was immediately referred to a psychologist,

who diagnosed me with clinical, or major, depression. It wasn't my first episode of depression, but it was definitely the worst.

My

husband was shocked when I told him the diagnosis, also because I’d kept the appointments

from him. I was shocked myself – I hadn’t been overly emotional, or had trouble

getting out of bed, or running my son to and from school. I was what the psych

called ‘high-functioning’, which means the traditional, if there is such a

thing, symptoms didn’t fit. But what I’d been doing – pushing myself harder,

convincing myself everyone would be better without me, beating myself up over

things I logically knew I couldn’t control, like whether a publisher would accept

my work – were also symptoms.

Over time,

working with the psychologist, my mental state improved.

What have

I learnt since?

Community is important. My writer’s group meets

monthly, but I needed more of a connection to the writing community to counter

the isolation I’d been feeling. Ellie Marney wrote a great post about finding her literary community online. I began

volunteering with Writers Victoria, partly to learn more about the industry, partly

to do something other than tie myself to a desk all day, every day. Also, other

writers get the whole talking to imaginary people in your head thing, and the importance

of decisions like present v past tense, first v third person.

It’s okay not to write. There’s pressure on

writers – often from ourselves – to always be working. If we’re not actually

writing we’re thinking about writing or attending writing-related events. It’s like

we have to prove to ourselves and others that we’re serious. Every salaried

worker has sick days, holidays, time off. Sometimes we all need to do something

else, somewhere else. It’s okay to switch off.

Look after yourself

first. Exercise.

Eat healthy food. Sleep. Take breaks. Maintain that machine. Clean those

dongles.

Know yourself. Recognise the difference between struggling with the work and struggling with your mental health.

It’s okay to ask for

help. This

goes for health issues and writing – seek help from the writing community when

you need it. Help each other out.

I know I’ve

learnt from my experience because I recognised when it started happening again.

I go in for more surgery next week – not major spinal surgery this time, but a procedure

that’ll hopefully prevent me needing it again (which was starting to look

likely). I started stressing about the impact this will have on my work, the

cost, the recovery period and the pressure this will put on the rest of my family.

I’m booked to go to Canberra for the next HARDCOPY session a month after

this surgery, I have application and competition deadlines before that, I need

to stockpile the freezer with enough food to last a nuclear winter.

Then I

had the brilliant idea of aiming to do a triathlon in 18 months, to prove to

myself that the surgery was needed.

Then I stopped.

I recognised what I was doing. I decided to bugger it. I can’t control how I’ll

recover. If I miss this competition deadline there’ll be another one. We can live

on takeaway for a week or two if we need to. So what if my son misses a sportsball

lesson or two?

Thank you for this post. I'm currently in pain, will probably have to give up my crappy door-to-door weekend only job, and feeling hopeless as a writer. I relate to what you have said. And by the way - you're doing brilliantly!

ReplyDeleteHi, Jill. That sounds tough. :( You're not a hopeless writer - your work is great and sometimes other things, like health, are more important. That's not a bad thing. Hope the pain gets better soon. X

ReplyDelete